Tuesday, October 31, 2006

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

Robert Moore

who teaches English here at SJ, will be reading from his new collection of poetry this Friday evening. He is a marvellous reader; it would be well worth your coming out even if I weren't offering bonus marks for a short review.

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Untitled Poem

[This is one of several successful assignments that will be posted here. All the posted assignments received an A- or above, and all demonstrate different ways in which the chosen question could have been addressed. The following poem, by Luke MacNeil, is written in the style of Beowulf:]

The following poem, titled Untitled Poem, was discovered within the cell wall of an abandoned sanitarium in Lower Upperton, New Brunswick. The author is unknown, though evidence suggests that the piece was written by a male patient of voting age, most likely a student who was interred at the sanitarium for a length of time. Attempts to date the poem have also met with a measure of difficulty. Most experts agree that the manuscript was written in late September, 2006, though a few notable scholars maintain that it could date back as far as mid-September, 2006.[1]

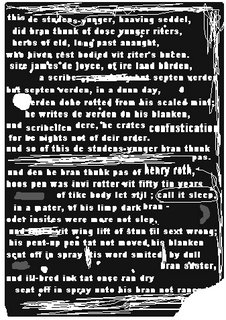

Rather than being written in Modern English (in the style of the time), Untitled Poem is instead written in a wholly unique script, a derivation of Modern English dubbed "Deviare English." It was deciphered in October 2006 by the Welsh linguist Sir Arthur Puffington, a man of questionable intelligence and sanity, and a professed schizophrenic (an assertion disputed by doctors). The script itself is of particular note. As described by Puffington in his journals, "...the penmanship is meticulous, however the paper is littered with various marks and scribbles, which seem to indicate an unsettled mind. In addition to this, the piece is scratched out on delicate carbon paper, somewhat odd for the time, given the relative abundance of ink and white paper." A portion of the original manuscript has been reproduced and directly follows this note (see page 3).

The following Modern English translation by A. L. MacNeill is generally considered of higher quality than Sir Arthur Puffington's original translation. There are, however, a few points of note. While the original manuscript was written in an alliterative verse based on stresses (a curious structure, more in the style of Old English than any modern poetry), MacNeill has formed his translation into a far more rigid structure, incorporating tetrameter to form a consistent beat and rhythm. Nevertheless, he manages to preserve much of the alliteration and caesura division that characterize the original piece. In addition to this, there is a small portion of the poem (several lines directly preceding the dream sequence) that were rendered unreadable through water damage. This has been noted in the text.

The culmination of two work-intensive days, the MacNeill translation has gained great esteem in literary circles. Indeed, most scholars agree that it will stand to be the definitive version of our time.

[1]See H. L. Puntiglio's paper "A Few Weeks, Does it Really Matter?" for more insight on this debate.

(Reproduced by permission of the Royal Puffington Society, Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada)

Hear now the tale of the student,

Frustration-filled and anger-fed,

His project due yet started not,

The young fellow at loss for words.

For weeks he walked his blank white halls,

And snapped the stalks of pencils slim

That cleave and splint like spines of slight

And fragile beasts; and crushed the

The poles of plastic pens, their blue

Ink fountained, and flood the floor

To soil and stain his sole-spent socks.

A hoard of holes did rent the walls,

And scores of blood-soaked bandages

Did bind his broke and trembling hands.

For days on days he paced those halls

Neglecting sleep, his thoughts silent,

His mind muted, capacity blocked.

His project due on the morrow

Without a word to show for it.

At last he sat at working desk,

Produced a pile of pure white sheets,

And moon-clothed pen, passed down to him

From father old, he who wrested

The silver stalk from claws yet stiff,

Those the family's fiendish banker,

While cold dead corpse lay untended

On top of its full funeral pyre.

The student thus, he settled down,

Did think of those fine writers past,

Of heroes old, long passed away,

Who wrestled might with writer's block.

Sir James the Joyce, of Irish birth,

A scribe of scarce but seven words

(Just seven words!) in but a day,

Those words well wrought from weighted mind;

He wrote the words on paper fair,

And copied there, confusion cried

For their order did him escape.

And then he thought of Henry Roth,

Whose pen was plagued with sixty years

Of quiet calm; call it sleep,

In a manner, of his lame brain -

Other organs were more awake,

And filled with flights of foul incest;

His pent-up pen which stayed his page

Discharged (its said) by dullard sis,

And ill-bred ink which once ran dry

Unloosed unto his willing cos;

And woe it was, his body well,

But mind maligned by selfsame act.

And then he thought of villain famed,

Mad Jack Torrance, whose old hotel

O'erlooked a leering length of maze

As twisted as his tortured brain;

When his writing had lost its way

He tried to tame his wife and son,

With winking edge of well-stoned axe;

He would not write in lieu of that,

And blamed them both for such his state;

For too much work and not much play

Made mad Jack Torrance a dull (brained) boy.

And thus he thought, the student still,

Of people past who've suffered same,

Until he fell beneath the spell

Of deep deceived and drowsy sleep.

[...][1]

The pictures played across his mind.

He dreamt himself a whitened sheep

With hollowed head, held in a pen,

His body bent upon a trough.

He chewed and spat and chewed again

His projects past, the papers mashed.

In time he tired of tripe-filled sup;

He gained some ground and hopped the fence,

And found his form in land of night,

Where star-strewn sky ruled over sun.

In dim-lit dales he saw the forms

Of suffering souls, like Sisyphus,

Rolling their rocks up rambling hills,

To have them roll back down again;

And faint-lit forms for freedom reached,

They clinched by chains to mountain tops

Where monkeys met with caps and wings

Did stab and slash with red-inked pens.

The sheep then saw a skull-capped sign,

Its arrow aiming down gold-bricked road.

For time on time, the sheep traveled

Until it came upon a field.

The fractured form of critic there

Did till the field with pole of wood,

She bent and browned with years of age

And wrapped in rags of words and text,

Her dress designed from sheaves of books.

Not crop of corn nor leaf of green

Did critic cull, but she instead

Grew crops of brain, round mounds of meat,

They fleshed and formed by craggy hand.

And all about the mind-full field

Some scarecrows sat, to scare the birds,

Their cratered crowns bereft of brain,

And filled instead with heaps of hair.

"Ho there," hollered the critic hag.

"A finer fleece I've never seen."

"I'd sell the stuff," (so said the sheep)

"But for a brain, as such you've sown."

"It's done,"she said, the deal declared.

The critic culled a ripened brain

From darkened deepness of the dirt,

And showed the sheep into her home,

And there the trade would consummate.

She strapped the sheep on stony slab

And split the skull with scalpel blade;

Then fixed the flesh into the head

And sewed the skull, now stitched and scarred.

She spun some gears and turned some cranks,

And sent the slab into the sky

Where lightning lived and lit the night;

Bold bolts caressed the bright device

'Till jagged jolt did strike the sheep

And leapt to life the planted brain.

And so the slab, its service done,

Did then descend back to the floor,

And then 'twas time for sheep to fill

Its end agreed to bargain full.

And so the sheep was shorn its wool,

But garish gleam did gilt the eyes

Of critic lean; she leched and leered

And drew from drawer a carving knife,

Then nicked the nose of naked sheep,

And put the piece into her mouth.

"Your wool is well," the critic said,

"But mounds of meat would fill my frame.

I'll cook you yet, and feast my fill."

From place to place the sheep did dart,

And critic chased, her knife o'erhead.

The house outgrown, outside they ran,

Where spark-filled sheep, still yet aglow

From lightning bolt, did light the night;

Jumped back and forth o'er garden fence.

The critic chased, did count the jumps;

Her eyelids fell with every leap

Till down she dropped, a dam asleep.

And sure the sheep did bound away,

With not its nose, nor still its wool,

Yet bountied brain made up the rest.

The student thus did wake from sleep,

His languid limbs yet still a-tingle,

And found his mind to be unblocked,

His project pent lay all exposed

To freshened frames of now-clear mind.

And so in such a schizoid twist

That thus recalls poor Philips Dick,

The student makes his laboured verse

An essay on it's own creation.

Do students dream of 'lectric sheep,

And wake to find their problems solved?

It seems that such was here the case.

[1]At this point in the text are four lines which are not readable.

Over the past several years, the epic Old English poem Beowulf has gained an increasingly larger distinction in our culture, its influence seen in everything from film to comic books. Nowhere is this influence more evident than in Untitled Poem, the subject of this project. Nearly every aspect of the poem, from its grammatical structure, to its lengthy digressions on mythic heroes of old, to its epic storytelling, has been clearly influenced by the literature of Old English, and its greatest debt is unquestionably owed to Beowulf.

The most curious influence of Beowulf on Untitled Poem can be found in its literary structure. Beowulf was written in an alliterative verse with four stresses per line, two stresses on each side of a dividing caesura. Where Untitled Poem has a more modern rigid structure (in this case composed in tetrameter), most of the other Beowulf features are present. Nearly every line has four stresses, divided in the middle by a distinguishable caesura. Alliteration has been used throughout the piece, generally following the style of Beowulf (with the alliteration on the first and second stresses, and the third and fourth where possible). In addition to this, the poem mimics Beowulf's sporadic use of kenning - hybrid words that are usually metaphoric in nature. Examples include "sole-spent"(used to describe the worn bottoms of the protagonist's socks) and "moon-clothed" (used to describe the silver coating on a pen). With all of these distinct grammatical features being relatively rare in modern poetry, it's fair to say that the poem has been influenced by Beowulf in most, if not all, of these aspects.

Grammatical similarities aside, more obvious comparisons can be seen in the content of the text itself. Just as the Beowulf poem contains numerous historical references and digressions, so too does Untitled Poem refer to its own "heroes of the past," figures who have faced a struggle comparable to that of the protagonist (in this case writer's block). Many of the references in Beowulf are somewhat vague and obscure (this is perhaps owing to the fact that people of the time were already somewhat familiar with the referenced stories, and did not need expansive digressions). This is mirrored in Untitled Poem, where only brief but suggestive explanations are given. The first "hero" mentioned is the Irish author James Joyce, who was notoriously finicky when it came to writing. A well-known anecdote is relayed in the poem, in which Joyce spends an entire day labouring over the writing and ordering of seven words.[1]

Following Joyce, there is a mention of American author Henry Roth. After writing his first novel, titled Call of Sleep (obliquely referred to in the line: "call it sleep, / In a manner, of his lame brain" ), Roth sustained a bout of writer's block that lasted for nearly sixty years. This is attributed (at least in part) to his admitted incestuous relationships with his sister and cousin (and the subsequent mental fallout that followed). The third reference in the poem moves away from the real-life literary "heroes" presented in the previous examples, and instead presents a fictional villain: Jack Torrance, the antagonist of Stephen King's novel The Shining. In the novel, Jack's struggle with writer's block is the catalyst for his descent into madness (a catalyst that is exploited by the novel's haunted Overlook hotel - the hotel itself is given an oblique reference in the line "whose old hotel / O'erlooked a leering length of maze / As twisted as his [Jack's] tortured brain). Finally, there is an obscure reference to author Philip K Dick in the poem's final lines. Dick spent much of his life battling mental illness, most notably schizophrenia. As a result of this, most of his novels and short stories deal with themes of alternate realities (including one of his more widely-read novels, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, which is also referenced in the poem's closing lines). Dick's themes have a twofold application in the poem. First of all, the writer enters an alternate reality (in this case a dream world) where, after a series of bizarre occurrences, he manages to solve his problem. The other influence can be seen in the fact that the project being laboured over in the poem is, in fact, the very poem itself (a meta-construct not unfamiliar to several works of literature, one of the best examples being Dick's novel The Man in the High Castle).

Yet for all of this, the poem's most obvious similarity to Beowulf is its theme of a hero undergoing a journey and overcoming an epic obstacle. In this case, the struggle is a more modern one than Beowulf faced (and one that was a non-issue in Beowulf's time): writer's block. The student's internal struggle is evident from the beginning (he stalks the halls, destroys writing utensils, rends holes in the wall, etc.). His quest to solve this problem is embarked upon once he enters the dream realm, where he overcomes various obstacles to regain his brain (thereby solving his writer's block). Yet rather than modeling the quest specifically on ancient mythological themes and subjects (swords, dragons, etc.), much of the dream is taken from relatively recent sources that have entered into our modern mythology: elements from L. Frank Baum's The Wizard of Oz (flying monkeys, the yellow brick road) and Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (various elements of body-horror) can be clearly seen in the protagonist's dream.

Despite these similarities, there are still a few points in which Untitled Poem differs from Beowulf. For instance, Beowulf's journey is a far more epic one, where he must overcome three obstacles instead of just one (the "rule of three," where the protagonist must overcome three obstacles, is a staple of literature, and one not evident in Untitled Poem). Also, Untitled Poem is treated with a far lighter and more comedic hand than was the epic Beowulf. Nevertheless, it's debt to Beowulf, whether looking at style, composition, or content, cannot be denied. The poem presents a credible example of a modern subject intentionally written in the classic Old English Beowulf style.

[1]There are several slightly different versions of the tale, though they typically go like this:

One day Joyce sat in his study, sprawled over his desk in a distraught state. A friend came in and asked what the matter was.

"I only wrote seven words today," said Joyce.

"But James," said the friend, "For you, seven words is superb!"

"Yes," said Joyce, cradling his head in his hands, "But I don't know what order they go in!"

Black, Joseph, ed. The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Medieval Period. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press. 2006. 36-37.

"Henry Roth." Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. 30 September 2006. 1 October 2006.

Jones, Miriam. Class Lectures. Saint John Campus, University of New Brunswick, Saint John, NB, 14/19/21 September 2006

"Rule of Three." Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. 10 Septemeber 2006. 1 October 2006.

Friday, October 20, 2006

Psychomachy

Psychomachy: a battle for the soul. The term comes from the Latin poem Psychomachia (c.AD400) by Prudentius, describing a battle between virtues and vices for the soul of Man. This depiction of moral conflict had an important influence on medieval allegory, especially in the morality plays.

from Chris Baldick, The Oxford Concise Dictionary of Literary Terms (1990)

War Medals

[This is the first of several successful assignments that will be posted here. All the posted assignments received an A- or above, and all demonstrate different ways in which the chosen question could have been addressed. The following is an ekphrasis:]

The kin crowded the laid out feast,

‘Round the heavily laden table

With men and boys boasting of a week’s worth

Of stories of working late and school mates

And all the endless toils.

Women working busily laying out the wares,

Refilling mugs and modestly accepting

Compliments on the full feast before them.

This is the way of the great gathering on Sunday,

A feast worthy of the working men it feeds, and the

Pride of the women who fashion it

After the group gathers in the sitting room around the

Roaring fire and with flames blistering and blazing

There heard beloved and ancient,

The story:

1917 was of the years

Men died for peace and glory.

My great uncle dear,

Lost his life, leaving us his story.

“Papa please show the medals,” an eager boy would say.

And always the dull, dirty tokens would be produced

And passed among the audience.

The ribbon on one is tattered and torn

But the red, white and blue stripes are clear.

The heavy, dull bronze is beaten and broke

Yet the strength of its meaning maintains,

For the family gathering ‘round to hear, its

History and heritage, a pride which none contains.

Looking now at its size, the medal fits neatly in

My glove

With a laurel wreath round the year,

The imperial crown above

Two crossed swords help form the star,

Was given to soldiers loved.

“Canadians serving overseas were granted such a token,”

Papa says, as his waiting family listens,

And again draws attention to the heirloom decoration.

On reverse, regiment written in stone, paired with the number

Of each war hero, proudly presented.

“The battle that beat our brave ancestor, gainer of such prize,

Was catastrophe like no other.

Trenches traced the battlefield, dirty dungeons for the soldiers

Sentenced to fight the German enemy.

Smoke, and shells thickened the air and choked the defenders.

The earthen holes, dug to shield our heroes, cave and collapse.

My great uncle and yours, lost his life in that dirty crypt.

He sailed,

November 1917, battle not won

To a field in Passendale.

We lost our beloved champion

And left only with his tale.

“So Papa, is his story all that is left?”

“Definitely not, my dear,” came a resonant reply.

“Bravery, duty and sacrifice are the life lessons learned.

Those virtues follow family through all weary and woe.

And though hardships may sometimes follow,

We have history and heritage to remind us that our

Path has been harder, and

Not only

Dirty tokens left behind,

From that grave cold and stony,

But a life kept in mind,

So we are never lonely.”

Sir Gawain and The Green Knight is written in the stock, bob and wheel form with deliberate use of alliteration throughout. “War Medals,” above, is written in an attempt to adhere to that form with the long, unrhymed verse as the “stock,” and the two syllable “bob” serves as an introduction to the four lined “wheel.” The “bob” and “wheel” follow the rhyming pattern ababa and tend to be much shorter lines than the “stock” portion. “War Medals,” contains random alliteration but Sir Gawain’s poet uses it skilfully and intentionally. The anonymous poet wrote during the alliterative revival and, “followed Anglo-Saxon poetic traditions, which used heavily stressed words at irregular intervals and alliteration” (Sir Gawain, 1). Sir Gawain and The Green Knight is highly structured and each word is deliberately written.

The poet elaborately describes material decorations and wealth by using an ekphrasis. An ekphrasis fully explains the detail and tangible aspects of the object but the poet’s purpose for using it is as layered and complex as the poem itself. The poem has meaning and symbolism layered so that the audience learns not to trust their instincts or initial response to events. The ekphrasis is a literary technique used for several different reasons. The obvious reason is to set a scene and describe people and the environment as a means of distinguishing class, wealth, and position. This is apparent through descriptions of Sir Gawain’s expensive shield and lavish environments displayed in his assigned room at the host’s castle. The more subtle and significant purpose of an ekphrasis is to symbolically remind the reader of predominant themes carried through the text. The description of Sir Gawain’s shield is heavily laced with religious reference and the moral code which he should be living by. The poet uses lengthy descriptions to reinforce the messages of good versus evil, worldly versus spiritual temptations, and the importance of virtue and community. The description of the luxurious furnishings of the guest chamber mirror the tempting wife’s beauty and symbolize that lush, tangible things can be deceiving. Religious reference and imagery subtly contrast greed, wealth, adultery and worldly goods which are all representative of mortal sin.

“War Medals,” explicitly describes the visible aspects of the war medals, their size, ribbons, texture, and emblem; but it also shows how a material thing can unite family and strengthen moral lessons taught in the past. The family gathers together carefree and happy to share a meal, as does King Arthur’s court in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. After their meal, they all gather around the patriarch and wait for stories to unfold and their relative’s heroic deeds to be praised. The war medals were chosen as an appropriate contemporary object because they represent valour, sacrifice, and duty. Sir Gawain’s tangible token is a green girdle which represents his own fallibility and weakness; but ultimately serves as a badge of wisdom, caution and humility for the community he returns to. In the “War Medals,” the tokens represent the death of a loved one, but also symbolize the strength to overcome obstacles and personal strife for the family who revere them.

The moral lessons and themes presented in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight are intricate and embody the spirituality of the time it was written. The themes are sometimes subtly layered and deliberate distracted away from, and other times blatantly presented. The “War Medals,” although secular and obvious, presents the message that hard times can be over come and good deeds live through the lessons they provide to the people aware of them. This message is delivered through the use of ekphrasis in describing the war medals.

References:

Baker, Chris. “The Long, Long Trail: The British Army in the Great War 1914-1918.” 1996. 22 September 2006.

Bradbury, N.H. “Memories & Diaries: A Gunner's Adventure.” First World War.Com: The War to End All Wars. September, 2001. 23, September 2006.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The Broadview Anthology of British Literature. Ed. Joseph Black, et al. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview, 2006. 235-304.

"Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: Introduction." Poetry for Students. Ed. Marie Rose Napierkowski. Vol. 0. Detroit: Gale, 1998. eNotes.com. January 2006. 23, September 2006.

“V.A.C Canada Remembers.” Veteran Affairs Canada. March, 2001. 22 September 2006.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

First Assignment

is marked and waiting to be picked up in the main Humanities and Languages office, Hazen Hall 100. I will bring them to class tomorrow, but in general, marked assignments will be on the shelf set aside for our class in HH100.

Marks are posted on WebCT.

If you handed in an assignment but have no mark, contact me.

Any questions, please contact me. I am happy to meet with you to discuss your assignment.

And don't forget: you have the option of rewriting. Hand in the new version, plus the original and my comments, within two weeks of tomorrow (i.e. by Nov. 2). If you need more time in order to go to the Writing Centre, let me know.

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Class cancelled today

Sorry for the short notice, but I am cancelling class due to a bad cold and sore throat. We will discuss Faustus on Thursday.

Monday, October 16, 2006

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

WebCT

Folks, a lot of you are concerned because WebCT says that you are late with an assignment when you have already handed it in. Ignore it! WebCT is set up so that students can hand in assignments electronically if they like, but as most people don't, they get flagged as not having handed anything in.

The only things you need to worry about in WebCT is checking your marks, and downloading the class presentations.

Friday, October 06, 2006

Exam

The exam for this course has been scheduled for Dec. 8 at 9am. Coffee cups and thermoses will be allowed.